Happily I digress (in fact, digression is the constant bugbear of my writing, a thing that more dedicated and professional writers either suppress or separate from their subject in order to provide themselves with material for subsequent projects. But I resent the tyranny of the paragraph and its flat surface. I prefer the space offered by digression, the sense that you are not walking over a piece of writing so much as into and through it, checking out this room and that one, a display here, a locked cabinet there. The digression gives the sense of moving not only into space but backwards in time, as if a turn off a path led you on a track that allowed you to see yourself as you were, on earlier points of the path, and by so doing reconsider both yourself and the path you took. That is the value of the digression. But it helps to keep notes). Because digression makes me happy.

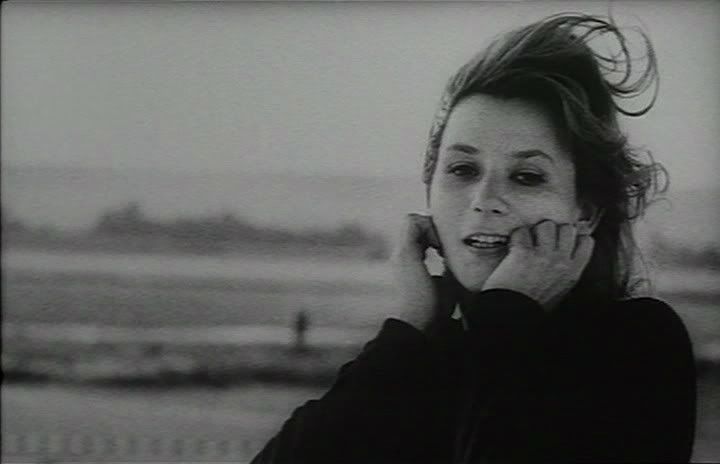

The trick with La Jetée, the thing that sends film critics into little spastic dances, is that it may not really be a film. Because there are no moving images in the whole thing. Instead you're treated to a series of black and white images against a soundtrack of almost intelligible whispers and racing heartbeats. The narrative is so sparse that we don't even learn the name of the time traveller or the woman he pursues or the scientists who keep sending him across time by means of a series of inhumanly cruel experiments (although he seems to spend the whole time in a kind of hammock, so it can't be too bad). All we do know about the man is that his waking life and dreams alike are fixated on an image from his childhood of a woman on a jetty, before the war that would level Europe and render the surface uninhabitable (another winning story point for me: humans forced to live in vast underground caverns).

'After the tenth day,' the narrator says, 'images begin to ooze like confessions'.

Images are the property of the past. Photographs show what has already happened, a fragment of an instant that will never recur in precisely that form again. Images suggest a structure and a pattern to things, showing us assemblages that appear to have been built just for that moment when the photo is taken. For us folk in the twenty-first century, images have become confused with memories, so much so that we often think of our past, especially the distant past, in terms of snapshots. Whether we've invented a technology that mimics memory or we've simply come to inhabit the technology, I don't know. But watching the images of La Jetée flit by will push you out of that place where memory and image cohabit. Anyway. See it, but avoid the dubbed version. And forgive the button-headed denizens of the future.

6 comments:

will do.

I am sure K will love it. He loves buttons and I love black turtlenecks.

And we love film.

tectonic plates = digression

According to my parents, 'button' was my first word. After that came 'ball'. Everything round to me was a ball, but buttons were (and still are) buttons.

If snapshots replace memory, then what is a memory of a snapshot? Like for instance, I'm remembering that face you unintentionally made (oozed like a confession, really) and subsequently deleted off of Hobsley's camera. Also, our Film department never questioned the integrity of La Jette as a film. At least not openly. Maybe our soft little first-year minds weren't quite ready for that argument. God, I really do go on. I should update my own weblog sometime.

Actually, La Jette is inarguably a film, given that film is nothing more than hundreds of thousands of still images in motion.

Film is a series of still images, but they're run together swiftly enough to provide the illusion of motion. La Jetee, it don't play that way. Instead we're left looking and thinking, "What is this thing?" There's a moment two thirds of the way through in which the images speed so that a woman appears to shift in her sleep. It's the imitation of film. It's a slide show, a filmstrip, a photo montage, and maybe it's a film. But it's not something or other, that's for sure.

A film?

Post a Comment