O happy evening. The Palinode and The Lotus arrive home from a restaurant. Mid-conversation.

The Lotus: I really want to write more of those letters, like that one to the guy who smelled of talcum powder.

The Palinode: I see. (pause) I'm sorry, did you say falcon powder?

The Lotus: What? No. What?

The Palinode: What's falcon powder?

The Lotus: I said talcum powder. What's falcon powder?

The Palinode: That's what I want to know.

The Lotus: I don't think it exists.

The Palinode: Is it powder made of falcons, or is it a powder for falcons?

The Lotus: It isn't - it wouldn't be made of falcons. Foot powder isn't made of feet, you weirdo.

The Palinode: Yeah, but what kind of applications would powder for falcons have?

The Lotus: I. Wouldn't. Know. We don't own a falcon.

The Palinode: It's a niche market.

The Lotus: Uh-huh.

The Palinode: For proper falcon freshness.

The Lotus: Why not.

The Palinode: But do the unsuspecting falcons know that they're powdering themselves with falcons?

The Lotus: I'm in a different room now.

Thursday, August 25, 2005

Bag-el

By reading this post, you agree to the terms and conditions of this site. You may copy and distribute this post to others free of charge. You may not attempt to disassemble or reverse engineer this post in any way, nor make any unauthorized changes to the contents without express shouted permission of the author. This post is provided "as-is" and does not come with a warranty or guarantee of any kind. If you find this post so unbearably stupid that it is a waste of time retroactively, too bad.

This morning a cow-orker sent out a company-wide email with the subject line "Bagels outside accounting". Oh no, thought me, a bag of bagels has left behind man's authority and set out on their own moral venture. What laws will this baker's dozen flout as they build their own alien society, one unrecognizable to humans but a shelter for the inscrutable bagel mind?*

First off, as I know that bagels are nothing if not stubbornly utopian, I'm betting that they will refuse to recognize property, currency and all the striving and getting that burden humanity in a market economy. Instead they will almost certainly opt for a network of agrarian collectives, bartering goods between colonies and maintaining little contact with the outside world. There they will build their gigantic bagel ovens and boiling vats, which day and night shall pour forth more of their kind. Some will willingly put themselves into bags and ship themselves off for consumption in order to garner funds for the collectives' major food source, which is cream cheese. The rest will spend their days at work and leisure, motion and repose, gradually erecting an edifice of bagel art and philosophy to rival our own. Or they'll just rip stuff off from us and insert the word 'bagel' here and there. Whatever happens, they will eventually end up competing with us for the last few cream cheese deposits left on Earth. A hellish future awaits the world as cream cheese extraction peaks and begins its inevitable decline. As supplies drop and the demand continues to ratchet up, you can expect those bagels to put aside their philosophy and pick up weapons** to gain control over their staple.

I couldn't let such a clear threat to humanity go unanswered. I left my desk and found the bag of bagels on the little table next to the accounting office. Only four in the bag (had the rest gone before to make straight the way for some Oneida bagel colony?): two dark pumpernickel and onion, one plain, and another a complex of brown spots and mottles of blood red. Plus some cream cheese on the side.

"What's the red one?" I called out.

"That's chocolate raspberry," someone answered.

Chocolate raspberry. I understood the truth of the matter then. Cleary it was us who had failed the bagels. After such cruelty, what more could they want with human socitey? Let them have their cream cheese. Let them rain down their delicious but deadly missiles on our cities, our towns, and all our works. We obviously deserve it.

*

*And where is the bagel mind? Our scientists have dissected countless bagels in vain, smearing on the exploratory cream cheese, testing the dark oniony bagel mass with teeth and tongue, but no seat of consciousness can be found. Maybe they have some kind of hive mind, with its motive centre resting in some bagel queen slumbering in a kosher bakery, quietly generating the axioms of bageldom. Yeah, that's probably it.

**Never mind the bagel mind, where is the bagel hand? The bagel limb? How do they get so much accomplished in a day?

This morning a cow-orker sent out a company-wide email with the subject line "Bagels outside accounting". Oh no, thought me, a bag of bagels has left behind man's authority and set out on their own moral venture. What laws will this baker's dozen flout as they build their own alien society, one unrecognizable to humans but a shelter for the inscrutable bagel mind?*

First off, as I know that bagels are nothing if not stubbornly utopian, I'm betting that they will refuse to recognize property, currency and all the striving and getting that burden humanity in a market economy. Instead they will almost certainly opt for a network of agrarian collectives, bartering goods between colonies and maintaining little contact with the outside world. There they will build their gigantic bagel ovens and boiling vats, which day and night shall pour forth more of their kind. Some will willingly put themselves into bags and ship themselves off for consumption in order to garner funds for the collectives' major food source, which is cream cheese. The rest will spend their days at work and leisure, motion and repose, gradually erecting an edifice of bagel art and philosophy to rival our own. Or they'll just rip stuff off from us and insert the word 'bagel' here and there. Whatever happens, they will eventually end up competing with us for the last few cream cheese deposits left on Earth. A hellish future awaits the world as cream cheese extraction peaks and begins its inevitable decline. As supplies drop and the demand continues to ratchet up, you can expect those bagels to put aside their philosophy and pick up weapons** to gain control over their staple.

I couldn't let such a clear threat to humanity go unanswered. I left my desk and found the bag of bagels on the little table next to the accounting office. Only four in the bag (had the rest gone before to make straight the way for some Oneida bagel colony?): two dark pumpernickel and onion, one plain, and another a complex of brown spots and mottles of blood red. Plus some cream cheese on the side.

"What's the red one?" I called out.

"That's chocolate raspberry," someone answered.

Chocolate raspberry. I understood the truth of the matter then. Cleary it was us who had failed the bagels. After such cruelty, what more could they want with human socitey? Let them have their cream cheese. Let them rain down their delicious but deadly missiles on our cities, our towns, and all our works. We obviously deserve it.

*And where is the bagel mind? Our scientists have dissected countless bagels in vain, smearing on the exploratory cream cheese, testing the dark oniony bagel mass with teeth and tongue, but no seat of consciousness can be found. Maybe they have some kind of hive mind, with its motive centre resting in some bagel queen slumbering in a kosher bakery, quietly generating the axioms of bageldom. Yeah, that's probably it.

**Never mind the bagel mind, where is the bagel hand? The bagel limb? How do they get so much accomplished in a day?

Monday, August 22, 2005

on listening to sufjan stevens

I cannot cannot stand compulsively humming tunes that praise The Jesus. This is what I get for listening to Seven Swans in the morning. It's great music to walk to work with at eight a.m., dappled dawn alight on pale poplar leaves while cabbage moths jitter and dragonflies in cobalt and gold slice sunbeams, oh sure. Meanwhile Sufjan sings songs about nice dresses and someone who woke him up, but then suddenly you realize he's really talking about Dual Citizen and The Intergalactic Dad, and it's too late - you're stuck singing folksy but elegant melodies inspired by Mr. Upstairs. It taints everything. Signing timsheets. Filling up a styrofoam cup at the Van Hutte machine (that's Dutch for Fucking Awful Coffee). Combing through your inbox for insignificant emails (there are no insignificant emails). Looking through your files for some lost invoice. I just can't let go and enjoy myself when Sufjan's screaming about Ol' Long White Beard* in my head.

*That's it, I'm all out of silly names for God.

nb. There's a bug on the wall next to the computer as I type. It looks a bit like a cross between a mosquito and a caraway seed. If it's a mosquito I'll definitely kill it, but if it's some inoffensive bug that only resembles a mosquito then I don't feel justified swatting it out of existence (I'm what you call a situational Janist). Bugs, I feel, should continue on with their bug lives unmolested. After all, there's not much wildlife to be seen in this city, aside from the occasional rabbit in the park. This is the prairies, where insects and grass are the whole of the ecology (assuming that bisons are a kind of hairy smelly insect). On the other hand, I hate caraway seeds, and the notion of a caraway seed with legs and wings, just looking for a nice slice of rye to ruin, is almost too much to bear.

Never mind, it's gone.

*That's it, I'm all out of silly names for God.

nb. There's a bug on the wall next to the computer as I type. It looks a bit like a cross between a mosquito and a caraway seed. If it's a mosquito I'll definitely kill it, but if it's some inoffensive bug that only resembles a mosquito then I don't feel justified swatting it out of existence (I'm what you call a situational Janist). Bugs, I feel, should continue on with their bug lives unmolested. After all, there's not much wildlife to be seen in this city, aside from the occasional rabbit in the park. This is the prairies, where insects and grass are the whole of the ecology (assuming that bisons are a kind of hairy smelly insect). On the other hand, I hate caraway seeds, and the notion of a caraway seed with legs and wings, just looking for a nice slice of rye to ruin, is almost too much to bear.

Never mind, it's gone.

the fine things I saw on my way to work today

A loose knot of wasps dancing over a lump of mud at the end of my steps.

Burst of startled gold dragonflies erupting from a patch of timothy grass by the #15 bus stop on Cornwall.

A dainty pointy-faced schizophrenic in heavy black boots and short white pants stepping carefully off the curb.

A kamikaze horsefly barrelling into the side of my nose as I cut through the park.

My strangled yelp, followed by an attempt to look like it wasn't me who just screamed at being hit by a horsefly.

A crumpet dusted with icing sugar masquerading as breakfast food.

A politician in a cream suit and wine shirt, face like a shaved ferret, speaking smooth unaccented French into his cell phone.

Cool hallways girding the pedestrian mall.

Lots of ladeez.

A grasshopper drifting sideways into a concrete wall.

The sound of the impact impossibly dry, dryer than kindling. And strangely loud. How did so much crackling crawl into a grasshopper's armour?

Cabbage moths whirling around thistles on the cut by the rail yards. A few kept pace with me as I passed by.

Burst of startled gold dragonflies erupting from a patch of timothy grass by the #15 bus stop on Cornwall.

A dainty pointy-faced schizophrenic in heavy black boots and short white pants stepping carefully off the curb.

A kamikaze horsefly barrelling into the side of my nose as I cut through the park.

My strangled yelp, followed by an attempt to look like it wasn't me who just screamed at being hit by a horsefly.

A crumpet dusted with icing sugar masquerading as breakfast food.

A politician in a cream suit and wine shirt, face like a shaved ferret, speaking smooth unaccented French into his cell phone.

Cool hallways girding the pedestrian mall.

Lots of ladeez.

A grasshopper drifting sideways into a concrete wall.

The sound of the impact impossibly dry, dryer than kindling. And strangely loud. How did so much crackling crawl into a grasshopper's armour?

Cabbage moths whirling around thistles on the cut by the rail yards. A few kept pace with me as I passed by.

Sunday, August 21, 2005

Tuesday, August 16, 2005

solidarity

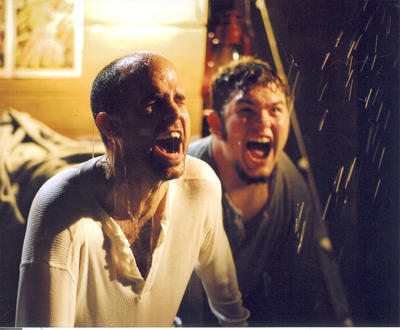

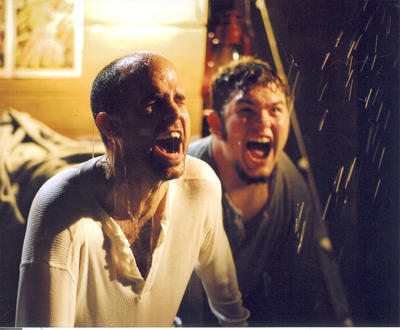

On Tuesday I visited the studio, where my reenactment crew were filming a shipping disaster. The DOP thought I would fill in handily as an extra for the scene in which the military ship rams the wooden schooner amidships and slices it neatly in half. I should have looked closer at the call sheets. My role: Hapless Fisherman #5. My task as extra: sit up in bed with a horrified look on my face, get tossed onto the floor, and then get doused with gallon after gallon of ice cold water. As the certainty of my fate closes in, I let out a howl of despair, for my own life, for the lives of my family, for those of my sad brave crewmates destined to find their rest at the bottom of the Atlantic (I'm the one on the left).

Then one of the set dec people dumped a bucket of water on me.

Jerks.

Then one of the set dec people dumped a bucket of water on me.

Jerks.

Monday, August 15, 2005

party

In Palinode's Palace two parties were thrown. One was held in the imaginary wing adjoining the chapel, the other in the abandoned cloister next to the hedge maze. The following is a conflation of both parties.

Saturday evening: we partied. Oh hot piranha, we partied. People streamed back and forth, along the hallway, eddying in the kitchen, smoking on the balcony, pulled into the living room and washing up on the couch. Until the break of 1:15, when everybody left to go home. That's right, people - run on home. When you were gone and it was just us and the finches, the real party rose up and started boogying across the hardwood. The real party lumbered from room to room, looking for passed-out guests, and finding none, started kicking the crap out of the furniture. Over went the couch. Floor lamp through the tv screen. Books afire. The hassock - unstuffed. The Markie Post poster - violated. Pint glasses smashed and pressurized widgets in Guinness cans fatally tampered with. Who can withstand so much sudden foam? At last, dawn wheeled over the elms and the party, deliquescent, blew away like a few last leaves. We were sleepy, spent, sticky, covered in new material (from the hassock) and finally in full possession of our new place. Later that afternoon we went to the beach.

Saturday evening: we partied. Oh hot piranha, we partied. People streamed back and forth, along the hallway, eddying in the kitchen, smoking on the balcony, pulled into the living room and washing up on the couch. Until the break of 1:15, when everybody left to go home. That's right, people - run on home. When you were gone and it was just us and the finches, the real party rose up and started boogying across the hardwood. The real party lumbered from room to room, looking for passed-out guests, and finding none, started kicking the crap out of the furniture. Over went the couch. Floor lamp through the tv screen. Books afire. The hassock - unstuffed. The Markie Post poster - violated. Pint glasses smashed and pressurized widgets in Guinness cans fatally tampered with. Who can withstand so much sudden foam? At last, dawn wheeled over the elms and the party, deliquescent, blew away like a few last leaves. We were sleepy, spent, sticky, covered in new material (from the hassock) and finally in full possession of our new place. Later that afternoon we went to the beach.

Friday, August 12, 2005

shed

The most mysterious room of my childhood was the shed in the sidelot. When we bought the house in 1979 the shed came along with the property, a little grey building leaning slightly at an angle with a tarpaper roof and a an untreated wood door clearly salvaged from some more ancient shed. A single window set in the back let in a beam of soft sunlight, but even so the shed was never brightly lit, the illumination somehow absorbed by old cobwebs and the dark glass jars left on the shelves by a previous owner. The inside smelled of mildew and motor oil. Wasps built nests in it.

At the age of nine I loved going out to the shed but feared it slightly. Partly I feared the pendulous paper nests that wasps built every summer. What truly attracted and repulsed me were the jars on the shelves and old pieces of equipment leaning in the dim corners (what they were I can't remember now). They bore the stamp of long-gone inhabitants, people who led alien lives. Our family had moved in from the city; we were from away, and even if we'd stayed there for decades we'd still be from away (we stayed ten years). The items in the shed were artefacts in a forgotten museum, and I was both visitor and curator. Eventually my father began to fill up the shed with his from away items: metal flasks of WD 40, a bright red jerry can, a weed whacker, blades for a table saw, racks of two by fours. The museum had been taken over, and only the mildewy smell and wasps remained.

After a year or so my father decided that the grey shed wasn't big enough to contain all the wood that he was storing in it, so he removed the wood and with it built a bigger shed. This one was roomier and cleaner and smelled of treated pine, with a rough splintery floor. The old shed went back to the wasps and the glass jars and the rough dirt floor.

By this time I'd picked up some friends from the neighbourhood - Willie, Dwayne, Derek, Darren. With a name like Aidan only confirming my from away status, I was clearly on the outer edge of the group - but I had the shed. I was like the weird guy at the party whom everybody tolerates because it's his party and he's supplying the venue. We started to spend our afternoons in and around the shed, hanging out in there, staining the seats of our rugby pants when we sat on the floor, safely out the upper-air wasp traffic (they ran the top half of the shed, we ran the bottom). Eventually someone decided that we'd obviously formed a club, and we lacked only a name to make it official.

Willie decided that our club name was to be The Cobras. He said he could even get us shirts with Cobras written on it. This was particularly cool name, I realized, because with a deadly name like The Cobras we were no longer a club - we were a gang. Ain't no one gonna mess with a bunch of ten year olds and their tilting-over shed if you see COBRAS written on the shed door. Especkally when we all step out in our jackets with COBRAS on the back, snazzy gold script with a golden cobra poised to strike emblazoned beneath. We were a long way from smoking, drinking, drugs, crime, cars, girls, sex, and shaving, but the jackets, even a few shirts, were a head start. All we had to do was give Willie two dollars each. Within a week we'd be up to our upturned collars in gang chic.

I had to go through only a small amount of begging for the two dollars. My parents handed over the money with a straight face. They were clearly more worried about me giving money to Willie, who was slightly older than the rest of us, than having a bona fide gang operating out of their sidelot.

About a week after we pooled our money, Willie showed up at the clubhouse with a white 3/4 black sleeve T-shirt, the kind that usually ended with AC/DC or Ozzy Osbourne transfers. Across his front, in blocky blue iron-on letters, ran the single word C O B R A. Willie sat down with us and told us that we were a gang now. He started assigning us various gang-related tasks. Darren was supposed to get some hockey sticks and a net so we could play in the street. His brother Duane was tasked with finding some Playboys for the clubhouse. I was supposed to clean up the shed, get my dad to kill the wasps, and maybe get a dartboard.

"Why don't you get the Playboys?" asked Duane.

"I went and got us the shirts!" Willie snapped.

"There's no room to play darts in here," I said.

"If we're gonna be a gang we need a dartboard in our clubhouse," Willie explained.

"I think my Dad's got a bunch of Playboys," offered Darren.

After a few more days it became clear that we were not getting our Cobras shirts. Nobody would ask about them, but with every afternoon meeting the tension grew, especially since Willie insisted on wearing his C O B R A shirt all the time. The longer it went on the more defensive Willie would get, pressuring us to do more and more of the work and all but daring us to bring up the subject of the shirts. Eventually the B started peeling off, threatening to turn our club into the Coras. Duane grew sullen, staring into the corner as Willie outlined our list of tasks. Darren left early one day and never came back. Those missing shirts were slowly destroying our gang.

I didn't care. As soon as Willie had stepped through the shed door with that Cobra shirt, I recognized the huge gulf between what I had imagined for our gang and what our gang really was - a few kids hanging around a smelly shed getting bullied by a short-tempered con artist. There were no purple jackets with gold emblazoning on the back (where had I gotten that idea?), no great vistas of coolness. There were only a few old Playboys and Mayfairs, which in a fit of guilt I handed over to my parents. My dad spent the afternoon leafing through them at the dining room table.

The gang officially disbanded (disganged?) later that summer when Willie's father Harold bought our shed. He had a plan to put it behind his barn and use it as a smokehouse. He ran a length of heavy chain around the shed, hooked the other end onto his truck and drove. The shed lurched and jumped through the air as if kicked by a great invisible boot. It thumped down on its side and dug into the ground, which was soft and damp from a day or two of rain. Even across the lot I could hear Harold swearing as he gunned the engine. After a few minutes he and Willie showed up with planks to wedge the shed out of the ground. Willlie was still wearing the shirt, which by now said C O R A.

After a lot of grunting and kicking, they had the planks wedged in under the shed. Willie gave me a nonchalant wave as they headed back to the pickup. They pulled away and the shed leapt free again from the planks, airborne and tumbling, wreathed about with bright metal, until it hit the ground once more, alternately bouncing along and digging in like a reluctant dog, until the truck pulled it out of sight. And that was that.

At the age of nine I loved going out to the shed but feared it slightly. Partly I feared the pendulous paper nests that wasps built every summer. What truly attracted and repulsed me were the jars on the shelves and old pieces of equipment leaning in the dim corners (what they were I can't remember now). They bore the stamp of long-gone inhabitants, people who led alien lives. Our family had moved in from the city; we were from away, and even if we'd stayed there for decades we'd still be from away (we stayed ten years). The items in the shed were artefacts in a forgotten museum, and I was both visitor and curator. Eventually my father began to fill up the shed with his from away items: metal flasks of WD 40, a bright red jerry can, a weed whacker, blades for a table saw, racks of two by fours. The museum had been taken over, and only the mildewy smell and wasps remained.

After a year or so my father decided that the grey shed wasn't big enough to contain all the wood that he was storing in it, so he removed the wood and with it built a bigger shed. This one was roomier and cleaner and smelled of treated pine, with a rough splintery floor. The old shed went back to the wasps and the glass jars and the rough dirt floor.

By this time I'd picked up some friends from the neighbourhood - Willie, Dwayne, Derek, Darren. With a name like Aidan only confirming my from away status, I was clearly on the outer edge of the group - but I had the shed. I was like the weird guy at the party whom everybody tolerates because it's his party and he's supplying the venue. We started to spend our afternoons in and around the shed, hanging out in there, staining the seats of our rugby pants when we sat on the floor, safely out the upper-air wasp traffic (they ran the top half of the shed, we ran the bottom). Eventually someone decided that we'd obviously formed a club, and we lacked only a name to make it official.

Willie decided that our club name was to be The Cobras. He said he could even get us shirts with Cobras written on it. This was particularly cool name, I realized, because with a deadly name like The Cobras we were no longer a club - we were a gang. Ain't no one gonna mess with a bunch of ten year olds and their tilting-over shed if you see COBRAS written on the shed door. Especkally when we all step out in our jackets with COBRAS on the back, snazzy gold script with a golden cobra poised to strike emblazoned beneath. We were a long way from smoking, drinking, drugs, crime, cars, girls, sex, and shaving, but the jackets, even a few shirts, were a head start. All we had to do was give Willie two dollars each. Within a week we'd be up to our upturned collars in gang chic.

I had to go through only a small amount of begging for the two dollars. My parents handed over the money with a straight face. They were clearly more worried about me giving money to Willie, who was slightly older than the rest of us, than having a bona fide gang operating out of their sidelot.

About a week after we pooled our money, Willie showed up at the clubhouse with a white 3/4 black sleeve T-shirt, the kind that usually ended with AC/DC or Ozzy Osbourne transfers. Across his front, in blocky blue iron-on letters, ran the single word C O B R A. Willie sat down with us and told us that we were a gang now. He started assigning us various gang-related tasks. Darren was supposed to get some hockey sticks and a net so we could play in the street. His brother Duane was tasked with finding some Playboys for the clubhouse. I was supposed to clean up the shed, get my dad to kill the wasps, and maybe get a dartboard.

"Why don't you get the Playboys?" asked Duane.

"I went and got us the shirts!" Willie snapped.

"There's no room to play darts in here," I said.

"If we're gonna be a gang we need a dartboard in our clubhouse," Willie explained.

"I think my Dad's got a bunch of Playboys," offered Darren.

After a few more days it became clear that we were not getting our Cobras shirts. Nobody would ask about them, but with every afternoon meeting the tension grew, especially since Willie insisted on wearing his C O B R A shirt all the time. The longer it went on the more defensive Willie would get, pressuring us to do more and more of the work and all but daring us to bring up the subject of the shirts. Eventually the B started peeling off, threatening to turn our club into the Coras. Duane grew sullen, staring into the corner as Willie outlined our list of tasks. Darren left early one day and never came back. Those missing shirts were slowly destroying our gang.

I didn't care. As soon as Willie had stepped through the shed door with that Cobra shirt, I recognized the huge gulf between what I had imagined for our gang and what our gang really was - a few kids hanging around a smelly shed getting bullied by a short-tempered con artist. There were no purple jackets with gold emblazoning on the back (where had I gotten that idea?), no great vistas of coolness. There were only a few old Playboys and Mayfairs, which in a fit of guilt I handed over to my parents. My dad spent the afternoon leafing through them at the dining room table.

The gang officially disbanded (disganged?) later that summer when Willie's father Harold bought our shed. He had a plan to put it behind his barn and use it as a smokehouse. He ran a length of heavy chain around the shed, hooked the other end onto his truck and drove. The shed lurched and jumped through the air as if kicked by a great invisible boot. It thumped down on its side and dug into the ground, which was soft and damp from a day or two of rain. Even across the lot I could hear Harold swearing as he gunned the engine. After a few minutes he and Willie showed up with planks to wedge the shed out of the ground. Willlie was still wearing the shirt, which by now said C O R A.

After a lot of grunting and kicking, they had the planks wedged in under the shed. Willie gave me a nonchalant wave as they headed back to the pickup. They pulled away and the shed leapt free again from the planks, airborne and tumbling, wreathed about with bright metal, until it hit the ground once more, alternately bouncing along and digging in like a reluctant dog, until the truck pulled it out of sight. And that was that.

Monday, August 08, 2005

Sunday, August 07, 2005

nan golden shower of photos

On Friday I went to the zoo. For some people this is no great accomplishment - one quick drive and ten bucks later, they're staring at a tamarind in a branch or scanning a pile of rocks and wondering where the hell the African Porcupine is supposed to be. But the closest zoo to me lies over two hundred fifty kilometres away, so I have to take a plane to see the African porcupines. Don't believe me? I'll show you.

These people didn't get to come to the zoo with me. They looked a bit uptight.

I discovered that the zoogoers were even more uptight than the passengers on the plane. By the time they showed up at the entrance to the African Savannah enclosure (a bit oxymoronic, but it's an unavoidable aspect of zoos) they were clearly lost and dazed. These two had clearly wandered out of a 1980 Sears catalogue.

I snapped a picture of this man just as he stepped into a beam of bright sun. His wife was looking straight at me. I still can't quite figure out her expression.

My ostensible purpose there was to train a new field producer for upcoming shoots, but I'd really flown 800 km to hang out with the meerkats.

Apparently they shared an enclosure with the African porcupines, but I couldn't see them anywhere.

These people didn't get to come to the zoo with me. They looked a bit uptight.

I discovered that the zoogoers were even more uptight than the passengers on the plane. By the time they showed up at the entrance to the African Savannah enclosure (a bit oxymoronic, but it's an unavoidable aspect of zoos) they were clearly lost and dazed. These two had clearly wandered out of a 1980 Sears catalogue.

I snapped a picture of this man just as he stepped into a beam of bright sun. His wife was looking straight at me. I still can't quite figure out her expression.

My ostensible purpose there was to train a new field producer for upcoming shoots, but I'd really flown 800 km to hang out with the meerkats.

Apparently they shared an enclosure with the African porcupines, but I couldn't see them anywhere.

Thursday, August 04, 2005

basement

I don't get basements. Finished, unfinished, mildewed or bleached, boiler room to laundry room to teenage lair to adult den, basements are repositories of stillness and menace. Even the finished ones, with the mini bar in the corner and low shag carpet licking the cheap veneer baseboards and the bathroom chock full of kitschy bathroom crap and a toilet that needs plunging twice a week. Especially the finished basement, where the polyvinyl armature of civilization suffers the expeditious sowbug. Nothing dispels the minor charm of a basement den like the sight of a roach making a dash for the corner. Basements are graves that for some reason we have chosen to turn into rec rooms, fine and private places where an embrace is still an option. I don't get why we continue to create homes that include, along with the master bedroom and en suite tub, a sinkhole of angst. Maybe it's a trade-off: we now have so much casual luxury that we can afford an Egyptian-style tomb in our very own home, packed full of the little rewards that make life easy.

Basements are graves and graves are shuttles to the next world. Once they were boats that bobbed along to the far bank of the Styx. The last century turned them into spaceships arcing up to heaven or ferrying up through the clouds on a ramp of light. That's why movie aliens are so unremittingly hostile to us these days. They're the unwanted dead, re-animated and ugly and bent on returning their deaths to us from the celestial heaven we've dreamt up. Remember Close Encounters? Those aliens were children, emissaries of the future showing up with a positive message and a five-note phat hook for the baby boomers. Not a basement in sight. But War of the Worlds - that movie's all ours. That belongs to the generation that grew up in a basement, surfing channels and playing video games, sneaking in boys or girls and getting hammered, all the while growing to fit the dimensions of those rooms, accumulating toxins in the gills. We're ready for a movie where, when those aliens come, we run screaming and barricade ourselves in a choice basement. And what a surprise it is when the aliens get in.

Basements are graves and graves are shuttles to the next world. Once they were boats that bobbed along to the far bank of the Styx. The last century turned them into spaceships arcing up to heaven or ferrying up through the clouds on a ramp of light. That's why movie aliens are so unremittingly hostile to us these days. They're the unwanted dead, re-animated and ugly and bent on returning their deaths to us from the celestial heaven we've dreamt up. Remember Close Encounters? Those aliens were children, emissaries of the future showing up with a positive message and a five-note phat hook for the baby boomers. Not a basement in sight. But War of the Worlds - that movie's all ours. That belongs to the generation that grew up in a basement, surfing channels and playing video games, sneaking in boys or girls and getting hammered, all the while growing to fit the dimensions of those rooms, accumulating toxins in the gills. We're ready for a movie where, when those aliens come, we run screaming and barricade ourselves in a choice basement. And what a surprise it is when the aliens get in.

Tuesday, August 02, 2005

bird facts

Ever since I was a child, or maybe ever since I came to work today, I wanted to write an encyclopedia designed to be recovered after the apocalypse, when the ruined descendants of our once-proud race wander the barren lands of post-industria, drawing out from the poisoned sandy soil a few mean sprouts for their pots, huddling for shelter in the lee of concrete slabs hove up from the beds of underground parking lots and foundations of office buildings long since stumbled down onto their own footprints, economies old and new wiped away and replaced by an irradiated hunger and a savage bronze sky - well, when that all happens, I thought it would be cool if our mutated progeny found an encyclopedia on a foraging mission into one of the Zones of the Ancient Overlords (that's any urban area currently over 50 000) and returned with my gigantic book packed full of utter bullshit about everything. Here are some samples.

Bird - Although many ancient writings refer to birds, they do not in point of fact exist. Birds were invented as a piece of wish fulfillment by the ancient Athenians, who longed to defy gravity but did not have sufficient technology to imagine anti-gravity boots. They also supposed that birds would escort the souls of the dead down to the underworld. This was how dumb they were. No one was more surprised than the Athenians when the animals that they had made up to keep their mortal bodies company actually appeared. They still weren't real.

Species of birds - It was thought that the world held 10 000 species of birds, but we now know this to be nonsense. Look around you - how could so many birds fit into the world? We would be overwhelmed by such numbers. The truth is that there is only one species of bird, and since birds were never real in the first place, there is only one bird. But it is everywhere.

Composition of birds - Most birds are made of anodized aluminum. They can be broken down into over 2700 individual pieces, each one hand-milled by a certified Guild Member. Such birds can be heavy and cumbersome to the novice, but with a bit of practice and a good harness you'll find that the performance is worth the extra weight.

Dangers of birds - The chief danger posed by birds lies in the invitation they extend, in the mind of the beholder, of the bird's existence. Once the beholder accepts the reality of the bird, they are then vulnerable to attacks of beak, claw, and offensive trilling. Further exacerbation of this danger arises from the typical bird's composition of heavy metals (cadmium, vanadium etc.) and highly radioactive waste, not anodized aluminum as some sources would have it.

Here is a picture of a bird in its larval stage:

Note the delicate wing structure already emergent along the flanks.

Bird - Although many ancient writings refer to birds, they do not in point of fact exist. Birds were invented as a piece of wish fulfillment by the ancient Athenians, who longed to defy gravity but did not have sufficient technology to imagine anti-gravity boots. They also supposed that birds would escort the souls of the dead down to the underworld. This was how dumb they were. No one was more surprised than the Athenians when the animals that they had made up to keep their mortal bodies company actually appeared. They still weren't real.

Species of birds - It was thought that the world held 10 000 species of birds, but we now know this to be nonsense. Look around you - how could so many birds fit into the world? We would be overwhelmed by such numbers. The truth is that there is only one species of bird, and since birds were never real in the first place, there is only one bird. But it is everywhere.

Composition of birds - Most birds are made of anodized aluminum. They can be broken down into over 2700 individual pieces, each one hand-milled by a certified Guild Member. Such birds can be heavy and cumbersome to the novice, but with a bit of practice and a good harness you'll find that the performance is worth the extra weight.

Dangers of birds - The chief danger posed by birds lies in the invitation they extend, in the mind of the beholder, of the bird's existence. Once the beholder accepts the reality of the bird, they are then vulnerable to attacks of beak, claw, and offensive trilling. Further exacerbation of this danger arises from the typical bird's composition of heavy metals (cadmium, vanadium etc.) and highly radioactive waste, not anodized aluminum as some sources would have it.

Here is a picture of a bird in its larval stage:

Note the delicate wing structure already emergent along the flanks.

the illustrated p'node

I have of late - I know not wherefore - lost all my words. Therefore I give you pictures, from a roll of film that had been sloshing around in my desk drawer for a few weeks.

In June The Lotus and Self went camping out at a friend's farm, where we watched fireworks, ate like horrible pigs and broke the law within the chambers of our gut,the roseate corridors of our bloodstream and the chemical bridges between axon and dendrite. You can read about it in great detail over here. We also brought a tent, but since neither of us are campers, we neglected to bring poles for the tent. Fortunately for us, The Lotus carries the magicked mummified hand of MacGyver in her backpack, so we tied the tent to a branch, staked it to the ground, draped a tarp over the branch as a token against the elements. And what a sorry-ass motherfucker it turned out to be:

And that was the tent at its best, before the evening rainclouds dropped half the Pacific Ocean on us. After that things took a turn for the soggy. Here's my shadow.

The strange bulge between my legs is either my backpack or my way oversized scrotum again.

After we set up the tent we met this little girl, who, with her gleeful expression and clasped hands, reminded me of a nun on crystal meth.

I wasn't far off. Within seconds her cherubic facade cracked and she lashed out with furious fists at all foolish enough to approach.

It was like being caught in a tiny human hurricane of bruises. It's okay, you don't have to believe me. I know what's true in this world. What's true is what I tell myself in my office.

Speaking of true things, here's a picture of my wife from a trip to Saskatoon a week or two later. She's the one on the left.

The long-haired shadow on the right is her friend Frances. Here's Batty, who was also sitting with us.

And here's another friend of mine. We call him Starcat. He updates infrequently, enjoys mathematical puzzles, cats, walks in the park. Turn-ons: women with glasses, women without glasses. Turn-offs: people who comment on his morphing arm.

For a brief while a girl named Theresa showed up, looked a bit bored, read a bit, wandered off. She seemed nice. I took her picture.

Lastly, here is a car that I've watched corrode slowly over the last five years. No one will fix it, no one will plate it, no one will take the time to come and turn it into a little cube of metal. Instead it rusts, indifferent to sun and rain. I dig the mufflers.

In June The Lotus and Self went camping out at a friend's farm, where we watched fireworks, ate like horrible pigs and broke the law within the chambers of our gut,the roseate corridors of our bloodstream and the chemical bridges between axon and dendrite. You can read about it in great detail over here. We also brought a tent, but since neither of us are campers, we neglected to bring poles for the tent. Fortunately for us, The Lotus carries the magicked mummified hand of MacGyver in her backpack, so we tied the tent to a branch, staked it to the ground, draped a tarp over the branch as a token against the elements. And what a sorry-ass motherfucker it turned out to be:

And that was the tent at its best, before the evening rainclouds dropped half the Pacific Ocean on us. After that things took a turn for the soggy. Here's my shadow.

The strange bulge between my legs is either my backpack or my way oversized scrotum again.

After we set up the tent we met this little girl, who, with her gleeful expression and clasped hands, reminded me of a nun on crystal meth.

I wasn't far off. Within seconds her cherubic facade cracked and she lashed out with furious fists at all foolish enough to approach.

It was like being caught in a tiny human hurricane of bruises. It's okay, you don't have to believe me. I know what's true in this world. What's true is what I tell myself in my office.

Speaking of true things, here's a picture of my wife from a trip to Saskatoon a week or two later. She's the one on the left.

The long-haired shadow on the right is her friend Frances. Here's Batty, who was also sitting with us.

And here's another friend of mine. We call him Starcat. He updates infrequently, enjoys mathematical puzzles, cats, walks in the park. Turn-ons: women with glasses, women without glasses. Turn-offs: people who comment on his morphing arm.

For a brief while a girl named Theresa showed up, looked a bit bored, read a bit, wandered off. She seemed nice. I took her picture.

Lastly, here is a car that I've watched corrode slowly over the last five years. No one will fix it, no one will plate it, no one will take the time to come and turn it into a little cube of metal. Instead it rusts, indifferent to sun and rain. I dig the mufflers.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)